Last night I was privileged to be part of a panel at the Tate Modern holding a discussion with each other and the audience on “What can murals do?”. Each panelist gave a 5 minute presentation. This was mine.

I’Il tell you what I don’t like. I don’t like statues. They literally place one person on a pedestal for achievements of the many. But I love murals as a beautiful expressive form to celebrate collective struggles. They use the everyday urban fabric to remind us: something momentous happened here. They summon us to action today.

Three examples are especially meaningful for me, but I hope they will resonate with you too, in these times. They are about courageous uprisings from below – the dignity of resistance against oppressors, persecutors, exploiters and fascists.

The first commemorates the iconic clash of fascism and anti-fascism on 4 October 1936, when thousands of uniformed, jackbooted fascists, inciting violence and hatred, sought to invade the streets where tens of thousands of working class Jews eked a living, They tried to win the local Irish Catholic community against the Jews. On the day the most bloody clashes were in Cable Street, where many Irish united with Jews to build barricades, to physically stop them. The fighting was with the police, ordered by the Home Secretary to facilitate the fascists free speech and movement.

The mural graces the side wall of St Georges Town Hall on Cable Street. It was commissioned In 1976 after a campaign by local writers, poets, artists who hatched their cultural creations in the basement of that building.

Every 5 years there is a memorial march. In 2016 I was convenor of Cable Street 80. We marched from Altab Ali park in Whitechapel – named for a young Bengali sweatshop worker murdered in a racist attack in 1978 – to a rally near the mural. The artwork is so dramatic, you can almost hear it. One commentator wrote: “Every space has action, perspective is a whirlpool.” For me It is a clarion call for resistance today.

Also in 1976, when work began in Cable Street, an industrial dispute broke out in a photo processing factory in Willesden, mostly staffed by poorly paid “citizens of Empire – South Asian migrant women plus Irish and Caribbean workers. When one worker was dismissed for allegedly working too slowly, some fellow workers immediately came out in solidarity. When a manager compared workers to “chattering monkeys”, Jayaben Desai replied ‘What you are running here is not a factory, it is a zoo. In a zoo, there are many types of animals. Some are monkeys that dance on your fingertips, others are lions who can bite your head off. We are the lions, Mr. Manager’. She led a walk out of 137 workers. An uprising.

Union groups across Britain came to the picket lines – the most remarkable, miners from Yorkshire’s white monocultural pit villages gave solidarity to Asian women migrant workers. Postal workers boycotted the company. Students came too. I nursed a large bump below my knee on the way back to Leeds Uni after a policemen kicked me. This fight for union recognition won great community support.

In difficult times, economically, the two year strike ultimately failed but inspired campaigns for change. It is celebrated in two murals unveiled in 2017 – one in a small backstreet opposite the factory site, now converted into flats. But on the main road, Dudden Hill Lane, is a stunning 28metre-long mural created in community workshops facilitated by artist Ann Ferrie. Participants included families of the strikers and schoolchildren. Archive photographs from the strike became stencils that were screenprinted, photographed, then digitally composited into artwork and printed on to boards. People of all artistic abilities saw their work in the final piece.

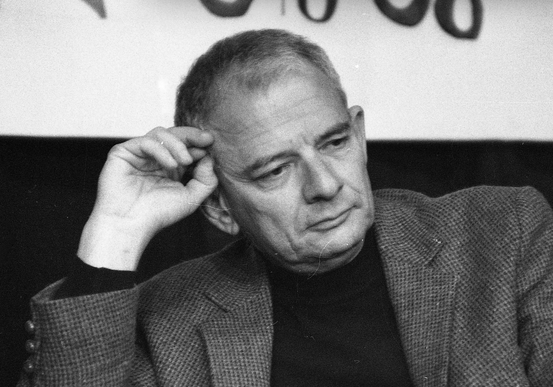

We travel eastwards for my third example in the heart of what was the Warsaw Ghetto from 1940-43. A mural on a school building by, Dariusz Paczkowski, depicts a defiant Marek Edelman, a daffodil in his fist, and a brick wall. Edelman, a Jewish marxist, and anti-nationalist, was Second in Command in the three-week uprising of a few hundred starved combatants with improvised weapons against the armed might of the Nazis. He wrote a searing memoir called The Ghetto Fights and always stressed it was a collective uprising whose participant had already survived two and a half years in the ghetto through a culture of mutual aid and countless quiet acts of daily resistance by so many.

I met him briefly in 1997. Last year I was in Warsaw for the 80th anniversary of the ghetto uprising. I took part in the alternative ceremony led by grassroots anti-racist and anti-fascists, in contrast to the militaristic official ceremony, brimming with Polish and Israeli flags.

Edelman died in 2009. He pioneered these alternative ceremonies, knowing that this history belonged neither to Polish nor Israeli nationalists. He said “we fought for dignity and freedom not for territory nor for a national identity.”

The words in Polish on this mural could not be more apt today. “Hatred is easy. Love requires effort and sacrifice.”

Warsaw 19th April, 2019, 12 noon. Crowds gather either side of the 11 metres high Ghetto Fighters’ monument made of granite that, ironically, was sourced by the Nazis. They intended to build a monument to mark their victory in Warsaw. They never did. Warsaw was a city of resistance. They would have had to build it on rubble in any case. Their only way of suppressing the people of Warsaw, ultimately, was by destroying large sections of it. They ghettoised the Jews who had made up a third of the city’s pre-war population, and deported most of them to the death camp at Treblinka. They put down a remarkable, three-week long guerrilla campaign by hundreds of barely-trained fighters aged from 13-40 years of age. They terrorised Warsaw’s non-Jews, defeating the uprising they led 16 months later. Small numbers of Jews who survived the burning of the ghetto in 1943 were hidden but emerged to fight in the ’44 city uprising.

Warsaw 19th April, 2019, 12 noon. Crowds gather either side of the 11 metres high Ghetto Fighters’ monument made of granite that, ironically, was sourced by the Nazis. They intended to build a monument to mark their victory in Warsaw. They never did. Warsaw was a city of resistance. They would have had to build it on rubble in any case. Their only way of suppressing the people of Warsaw, ultimately, was by destroying large sections of it. They ghettoised the Jews who had made up a third of the city’s pre-war population, and deported most of them to the death camp at Treblinka. They put down a remarkable, three-week long guerrilla campaign by hundreds of barely-trained fighters aged from 13-40 years of age. They terrorised Warsaw’s non-Jews, defeating the uprising they led 16 months later. Small numbers of Jews who survived the burning of the ghetto in 1943 were hidden but emerged to fight in the ’44 city uprising. pink/purple banner has the slogan “We will outlive them!” in several languages including Yiddish – the mother tongue of Warsaw’s Jews that Hitler’s forces tried to to bury with the Jews. But on this day, nearly 75 years after Hitler died, Yiddish words are again sung on Warsaw’s streets.

pink/purple banner has the slogan “We will outlive them!” in several languages including Yiddish – the mother tongue of Warsaw’s Jews that Hitler’s forces tried to to bury with the Jews. But on this day, nearly 75 years after Hitler died, Yiddish words are again sung on Warsaw’s streets. resistance in Nazi-occupied Poland. Alongside the Bund flags is one with the International Brigade colours celebrating those who left Poland to fight Franco’s fascists in Spain. One side of the banner is in Yiddish – underlining the role played by internationalist Jews in the Naftali Botwin company of the Dombrowski Battalion.

resistance in Nazi-occupied Poland. Alongside the Bund flags is one with the International Brigade colours celebrating those who left Poland to fight Franco’s fascists in Spain. One side of the banner is in Yiddish – underlining the role played by internationalist Jews in the Naftali Botwin company of the Dombrowski Battalion. from a Warsaw school that emphasises its multicultural curriculum, sings resistance songs in Yiddish. Few, if any of them, are Jewish but their diction is perfect and their identification with the meaning of what they sing shines through. Some songs are familiar, others new to us. We had spent the previous evening with “Warszawianka” – a revolutionary choir who led a workshop with us in the working class district of Praga.

from a Warsaw school that emphasises its multicultural curriculum, sings resistance songs in Yiddish. Few, if any of them, are Jewish but their diction is perfect and their identification with the meaning of what they sing shines through. Some songs are familiar, others new to us. We had spent the previous evening with “Warszawianka” – a revolutionary choir who led a workshop with us in the working class district of Praga. before we move over to the sculpture of a shattered world to represent the courageous Bundist, Szmul Zygielbojm who committed suicide in London as a political act, having read of the final destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, and the allies’ failure at the Bermuda Conference to propose drastic rescue action. This monument is particularly poignant for us, as it was our group working together with Bundist survivors, who established a plaque for Zygielbojm in London in the 1990s. Here the cracks in the shattered world are soon crammed with daffodils, the flower resembling the Yellow star in bloom, which Nazis made Jews wear in Germany, and some other lands under Hitler’s regime. The Bundist, Marek Edelman, the last surviving member of the command group that led the Ghetto Uprising, brought daffodils to such ceremonies until he died in 2009

before we move over to the sculpture of a shattered world to represent the courageous Bundist, Szmul Zygielbojm who committed suicide in London as a political act, having read of the final destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, and the allies’ failure at the Bermuda Conference to propose drastic rescue action. This monument is particularly poignant for us, as it was our group working together with Bundist survivors, who established a plaque for Zygielbojm in London in the 1990s. Here the cracks in the shattered world are soon crammed with daffodils, the flower resembling the Yellow star in bloom, which Nazis made Jews wear in Germany, and some other lands under Hitler’s regime. The Bundist, Marek Edelman, the last surviving member of the command group that led the Ghetto Uprising, brought daffodils to such ceremonies until he died in 2009 Marek Edelman dissented and sought to escape through the sewers. As we walked towards Mila 18 we were found among the crowd by Hania Szmalenberg, who earlier in the week walked us through the memorials and showed us how she had re-landscaped the original memorial and and added one in English, Polish and Yiddish closer to the road.

Marek Edelman dissented and sought to escape through the sewers. As we walked towards Mila 18 we were found among the crowd by Hania Szmalenberg, who earlier in the week walked us through the memorials and showed us how she had re-landscaped the original memorial and and added one in English, Polish and Yiddish closer to the road.

overshadowed today by tall glass towers recently built by business corporations. It is far from the memorial route of Jewish martyrdom which crosses the north of the ghetto. Many visitors to Warsaw, following that memorial route in order to gain an insight into the history of the ghetto and the courageous resistance that fought there, do not reach this remarkable installation, unveiled in 2010, that stands where the fighters emerged from the sewers. It portrays a sewage canal rising vertically from the ground with disembodied hands symbolically climbing their way to freedom.

overshadowed today by tall glass towers recently built by business corporations. It is far from the memorial route of Jewish martyrdom which crosses the north of the ghetto. Many visitors to Warsaw, following that memorial route in order to gain an insight into the history of the ghetto and the courageous resistance that fought there, do not reach this remarkable installation, unveiled in 2010, that stands where the fighters emerged from the sewers. It portrays a sewage canal rising vertically from the ground with disembodied hands symbolically climbing their way to freedom.

She claimed that Jeremy Corbyn had crossed that line ( slandering him again as an antisemite, with the same lack of evidence but more self-control).

She claimed that Jeremy Corbyn had crossed that line ( slandering him again as an antisemite, with the same lack of evidence but more self-control). of solidarity – for one, and against the other – as the fight against antisemitism and for Palestinian rights are actually part of the same fight… if you believe in equality.

of solidarity – for one, and against the other – as the fight against antisemitism and for Palestinian rights are actually part of the same fight… if you believe in equality. Edelman saw no distinction and no contradiction at all between fighting for peace with justice and full equality for Palestinians, and fighting to his last breath against any expression of antisemitism. He did both courageously to the best of his ability at every stage of his life.

Edelman saw no distinction and no contradiction at all between fighting for peace with justice and full equality for Palestinians, and fighting to his last breath against any expression of antisemitism. He did both courageously to the best of his ability at every stage of his life.