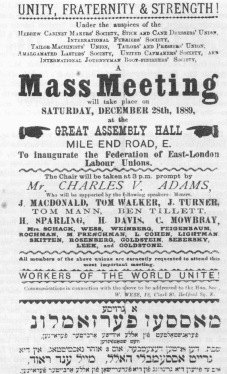

In honour of the 130th anniversary of London’s first May Day march in 1890, there will be blog posts throughout May on this site.

T is for Tillett and Thorne,

U is for Union of Women Matchmakers

In his book The Anarchists, set in London in 1887, the Scottish-German writer John Henry Mackay described London’s East End as “the hell of poverty” and the “Empire of Hunger”. This district bordered the City of London where enough wealth was made to build an Empire, then more fortunes were amassed from that empire. But they did not trickle down. How was it possible for grinding poverty and immense wealth to rub against each other without eventually sparking rebellion?

But Karl Marx’s comrade and sponsor, Friedrich Engels, thought the prospects of revolt were slim. In early 1888, He wrote to the writer/social commentator Margaret Harkness: “Nowhere else in the civilized world are the people less actively resistant, more passively submitting to their fate than in the East End of London.”

Suddenly, it all kicked off, first in a match factory in Bow, among the most exploited and disadvantaged sections of the labour force: girls and women, many of them also of Irish heritage – a community struggling to be treated as equals.

Their example was taken up by male workers in the Gas Works and Docks. In the struggles of 1888 and ’89, a “New Unionism” was born – one of its early products was the Union of Women Matchmakers established during a successful two-week strike at the Bryant and May factory that employed 1,400 women. After the spark was lit, a key role was then played by two trade union leaders, Will Thorne and Ben Tillett, whose personal experience of workplace exploitation began at the ages of 6 and 7 respectively.

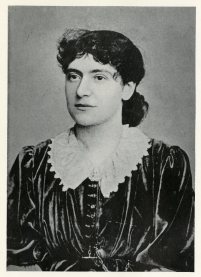

The strike by women at Bryant and May’s factory was precipitated by the management’s zealous  over-reaction after exploitative and unhealthy conditions there had been exposed in a small circulation left-wing newspaper. The author, Annie Besant, struck a nerve because Bryant and May were Quakers who cast themselves as slave abolitionists and enlightened employers. Besant told of long shifts, paltry wages, and petty fines frequently imposed on the flimsiest basis.

over-reaction after exploitative and unhealthy conditions there had been exposed in a small circulation left-wing newspaper. The author, Annie Besant, struck a nerve because Bryant and May were Quakers who cast themselves as slave abolitionists and enlightened employers. Besant told of long shifts, paltry wages, and petty fines frequently imposed on the flimsiest basis.

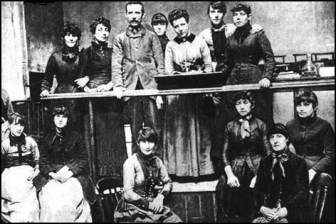

Foremen asked the workers to sign notes confirming they were happy their conditions. They met mass refusal. A gaggle of alleged “ringleaders” were sacked. Despite the absence of a union, as word got round the plant, women walked out spontaneously on strike. They picketed to stop any scab labour, held open-air meetings on free speech pitches; marched to parliament, forced the media to notice them, and rallied material and political support for their cause.

Managers threatened to import unemployed girls from Glasgow to replace them, or relocate to Scandinavia. The workers knew this was bluster. They formed a Union of Women Matchmakers and demanded that the sacked “ringleaders” were reinstated; that the whole system of fines was binned; and that management commit to building a separate eating area, as their food was getting contaminated on their long shifts by unhealthy work materials, and women were going down with “phossy jaw”.

They fought – and they won.

The match factory closed in 1979, and its 275 remaining workers made redundant. In 1988 its building started to be converted into a gated community of luxury flats. On the outer wall a plaque celebrates Annie Besant implying that she led the strike. She didn’t. That was led by the workers themselves such as Mary Driscoll, Alice France, Eliza Martin, Kate Slater and Jane Wakeling, who apparently had been involved in earlier unsuccessful strikes.

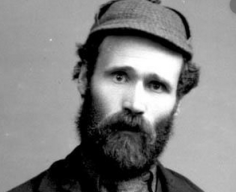

Will Thorne

Further east from Bow were London’s largest gas works at Beckton. Employees there were unionised by Will Thorne, a worker and agitator in his early 20s who had to overcome a major personal barrier. Neither he nor his wife could sign the marriage register on their wedding, as they were illiterate. He was working a 12-hour day at 6-years-old at a rope-makers in Birmingham. But he had great organisational and oratory skills, honed in open-air speeches for the Social Democratic Federation. He learned to read in his mid-to-late 20s with help from a union colleague, one Eleanor Marx!

At Beckton Gas Works there were two 12-hour shifts generating power round the clock. When management introduced a technological advance, instead of it easing the work burden, workers had to meet new targets and, on a rota basis, they were working occasional 18-hour shifts as well.

While low wages made life hard, Thorne believed that workers’ time was ultimately more valuable to them than money. His union committee him convinced them to fight collectively for an 8-hour day. He welcomed colleagues to a a huge workers’ meeting on 31 March 1889 as “Fellow Wage–Slaves”. Thorne promised them that if they “stand firm and don’t waver, within six months we will claim and win the 8-hour day, a 6-day week and the abolition of the present slave-driving methods in vogue not only at the Beckton Gas Works, but all over the country.”

This unionisation drive came at an apposite moment. The electricity industry was growing and beginning to challenge gas. When Thorne knew they had thousands of workers unionised his committee petitioned their employers saying that they had the strength to go on strike but they would rather negotiate a new deal for workers. Ultimately their employers, fearful of a strike, agreed. Negotiations took several weeks as productivity matters were ironed out. In the resulting deal, two 12 –hour shifts became three 8-hour shifts as more workers were taken on, and shorter hours were gained at no loss of pay.

Despite Thorne’s struggles with literacy, he later became the Labour MP for West Ham and went on to write his autobiography, My Life’s Battles.

Meanwhile, a former navy junior, then shoemaker, called Ben Tillett,was making a

Ben Tillett

name for himself locally as a trade unionist. In contrast to Thorne, Tillett’s working life began later – at 7-years-old – in a Bristol brickyard. His home life was abysmal. His birth mother died young, replaced with stepmothers who served the demands of Tillett’s alcoholic father, while neglecting or mistreating him. On his third attempt, he successfully ran away from home, joined a travelling circus and learned acrobatics. One of his five sisters tracked him down and took him to stay with relatives where he gained two years’ education before resuming his working life.

While Thorne was organising Gasworkers, Tillett, who had moved to Bethnal Green in east London where one sister lived, was attempting to unionise dockers in a largely casualised working environment, where workers endured the humiliating daily call–on. If they got work that day they were only guaranteed 2-hours. Tillett graphically described the atmosphere in the shed where the call-on happened in a pamphlet – The Dock Labourers Bitter Cry. He kept a diary. His last entry in 1888 read: “Cold worse than ever. Went to chapel. Old year out. Like to live next year a more useful life than last”.

He did. In mid-August 1889, the growing Tea Operatives and General Labourer’s Association made links with the Amalgamated Stevedore’s Union and, in response to a set of disputes that had begun with their employers, announced that the dockers were on strike. Tillett was the key figure among a collective strike leadership. In the first week, 10,000 workers were on strike. That grew massively as other dockers and workers in factories and warehouses, especially in dock related areas came out.

By the beginning of September, the local newspapers described (in disapproving terms) the East End as infected with “strike fever”. Workers across the board “found some grievance real and imaginary” to come out on strike. The dockers listed their demands: the dockers tanner (six old pence) an hour and 8d for overtime; a minimum 4-hour call-on, and the right to organise a union throughout the dock. Organising strike pay for such large numbers was logistically impossible so they distributed meal tickets redeemable at supportive shops and cafes. The Salvation Army supplied thousands of loaves a bread each day and dockers’ wives organised rent-strikes to minimise outgoings.

They held huge marches, and spectacular community parades to Hyde Park, appealing for support form the West End. According to Thorne, Tillett possessed “a spark of genius”, as he organised a picket system of the whole London docks.

They held huge marches, and spectacular community parades to Hyde Park, appealing for support form the West End. According to Thorne, Tillett possessed “a spark of genius”, as he organised a picket system of the whole London docks.

Four weeks in, the main dock employers, who had tried to starve the workers back to the docks, offered some enticing deals to small groups of employees, but at this critical moment with the strike becoming shakier, help suddenlyarrived from far away. Many of the dockers were Irish Catholics (neighbours and families of matchwomen), as were many of the dockers in Australia. On hearing of the strike they collected for their brothers and began cabling over huge amounts of money to keep that strike going.

The employers were forced to negotiate. In negotiations mediated by Cardinal Manning a widely respected churchman, the dockers won their demands. Their union, renamed itself the Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers’ Union and emerged from the strike with 18,000 paid up members.

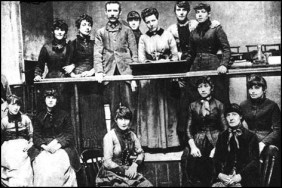

Meeting to form a matchwomen’s union

In each of these cases – the matchworkers, the gasworkers, the dockers all created or developed thier unions, but instead of the old “craft unions” of highly skilled workers, these were general unions, cheap to join, meeting the needs of the unskilled and low-skilled. This was the New Unionism.

Tillett and his close colleague Tom Mann wrote a pamphlet describing this phenomenon. In their new conception the work of trade unions went beyond just sorting out their own workplace “It is the work of the trade unions to stamp out poverty from the land.“ They would “work unceasingly for the emancipation of workers. Our ideal is the Cooperative Commonwealth.”

Ben Tillett… began working young. At seven years old he worked long days at Roach’s brickyard in Bristol, though he was probably relieved to get away from home, where his alcoholic father and a succession of stepmothers mistreated or neglected him. After two failed attempts to run away, he escaped with a circus troupe, who taught him acrobatics. He took a stray dog with him. The circus troupe gave him a Shetland pony to look after. At night he slept next to the pony, and the dog kept the rats away. One of Tillett’s five sisters tracked him down and took him to relatives in Staffordshire, where he had two years of schooling before being apprenticed to a shoemaker. At 13 he joined the Royal Navy, visiting various European ports, Philadelphia and the Caribbean, and learned to read and write with the help of a Scottish friend. Fittingly, in terms of his future activism, he sailed on one ship called Resistance. Between voyages he stayed with his sister’s mother-in-law in Bethnal Green, east London. He finally settled there at 16 years old, working at Markie’s boot factory, and joined the Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives.

Ben Tillett… began working young. At seven years old he worked long days at Roach’s brickyard in Bristol, though he was probably relieved to get away from home, where his alcoholic father and a succession of stepmothers mistreated or neglected him. After two failed attempts to run away, he escaped with a circus troupe, who taught him acrobatics. He took a stray dog with him. The circus troupe gave him a Shetland pony to look after. At night he slept next to the pony, and the dog kept the rats away. One of Tillett’s five sisters tracked him down and took him to relatives in Staffordshire, where he had two years of schooling before being apprenticed to a shoemaker. At 13 he joined the Royal Navy, visiting various European ports, Philadelphia and the Caribbean, and learned to read and write with the help of a Scottish friend. Fittingly, in terms of his future activism, he sailed on one ship called Resistance. Between voyages he stayed with his sister’s mother-in-law in Bethnal Green, east London. He finally settled there at 16 years old, working at Markie’s boot factory, and joined the Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives.