My philosophical engagement with religion did not last long. Despite going to a Jewish Primary School in Hackney, and attending kheder (Jewish supplementary classes) two nights a week and on Sunday mornings until I was 14, I can’t remember believing in God. My synagogue attendance – decided by my family rather than me, tailed off rapidly after my barmitzvah. From the age of 8, going to football on a Saturday afternoon was the ritual I really looked forward to on a Saturday, and the only place where I actually prayed – though I am not sure to whom. Of course I was not alone. When I stood on the terraces at West Ham on a Saturday afternoon I would see faces I had seen two or three hours earlier in shul (synagogue). For those who think synagogues – even those that are nominally orthodox – are places purely of worship, let me disabuse you. While prayers were being alternately sung and mumbled, at least as far as the khazan (cantor),the rabbi and other synagogue officials believed, I would be listening in to some of the conversations going on around me in the men’s section – family gossip, work troubles, horse racing and football news. My late friend and comrade Charlie Pottins used to describe the United Synagogue (mainstream orthodox) the kind which I attended as a place where “Jews pray in a language they don’t understand to a God they don’t believe in, for the security of a state they don’t want to live in.”

But, I had a sense of family obligation, and even in my early 20s, when it came to the High Holy Days – Rosh Hashona (New Year) and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) I would return to my parents’ home and go with them to the synagogue. That all ended after Rosh Hashona 1982. that was The. Last. Straw.

In addition to a bizarre prayer for the Royal family intoned every shobbos (Sabbath), the state whose security we prayed for was Israel. Only by now I was no Zionist. Just a few weeks before I had marched, in a large contingent, behind a large yellow banner of the Jewish Socialists’ Group in a demonstration some 25,000 strong, to protest the horrendous war Israel had unleashed in Lebanon that summer, its tanks roaring through the homes of terrified Lebanese and Palestinian villagers, heading for Beirut where Yasser Arafat and Palestinian forces were concentrated. It was the first time our group had taken a banner on a Palestine Solidarity demonstration, and it was the sole Jewish banner there.

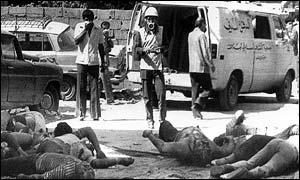

Just days before Rosh Hashona that year, there was the most sickening event of this whole war of destruction. Israel had allies within Lebanon – right-wing Phalangist Christian forces who hated the Palestinians with as much vigour as the Israeli commanders. Israel had asked local Phalangist forces to “clear out” any PLO fighters based in the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila. The Israeli army stationed troops at the exits of the camps and, at night they lit flares to assist the Phalangists in their task. Over a period of 36 hours a gruesome massacre of the residents of the camps children, women, men took place. Israeli officials acknowledged that there had been 700-800 deaths. The Palestinian Red Crescent estimate was 2,000. More than 1,200 death certificates were issued to survivors. Horrific photos in the aftermath showed indisputable evidence of mass executions.

after the massacre

It could not but be on the minds of those attending synagogues that Rosh Hashona. At that time the Jewish community where my parents lived, in Redbridge, was still expanding, and we went to High Holy Day services in a makeshift synagogue in a large room of the Redbridge Jewish Community Centre, nearer to our home than Ilford’s main purpose-built synagogue. Perhaps we came in a bit late but I remember sitting right at the back in the corner.

It was a period of transition in many branches of the United Synagogue. Those leading the services, and longstanding rabbis of some congregations, were being replaced by young, and sometimes charismatic adherents of an entryist, more orthodox, fundamentalist, movement, the Lubavitch. One of their rising young men, “educated” at a yeshivah (seminary) in Gateshead, was taking our service. Three-quarters of the way through the service came the sermon. This moment was usually marked by a few older people deciding they needed a toilet (actually cigarette) break, some temporarily taking their hearing-aids off, others gently closing their eyes for a few minutes. But most of the congregation would at least give the appearance of listening.

Having heard so many anodyne, safe sermons over the years, with stock religious platitudes that meant nothing to me, I was mentally switching off, when my ears pricked up. In his sermon this young Lubavitcher had started to comment on the war in Lebanon and the massacre that had just taken place at Sabra and Shatila. His words are still burned into me. “Jews have suffered 2,000 years of persecution. We should worry about a few hundred Palestinians who would grow up to be terrorists?” There was an audible intake of breath, then his sermon meandered off and people relaxed again. I wanted to run out screaming but was stuck right at the back in the corner with rows of people in front. I felt sick inside and my head was thumping. I struggled to sit through the rest of the service.

That was the last straw for me. Judaism, Jewishness, Israel, are all separate phenomena. You can appreciate Jewish culture without being religious. You can be a pious Jew and reject Zionism and so on… but what this person did was manipulate his position of power in a local Jewish community to tangle things together, in a religious context, to propagandise his racism, his fascistic variant of Zionism, his utterly inhumane political position.

I made a vow to myself never to return to synagogue for a service, save weddings, barmitzvahs etc. that I am invited to, which I’ve kept to. Many people are still fooled by the Lubavitch movement, who present themselves as vibrant, and charismatic in contrast to the more staid, conservative rabbis. But they are a cult of true fundamentalists, enticing people into their narrow ideological world which incorporates support for the most revanchist, intransigent, elements in Israel.

Israelis of “Yesh Gvul” (There is a Limit) protesting agaisnt the Lebanon invasion, 1982

The 1982 war in Lebanon, though, was also a watershed moment. The honeymoon period of diaspora Jewish support for Israel was starting to come to an end, and support for Israel among diaspora Jews has slowly declined since then. Within Israel itself, the Yesh Gvul movement of army refuseniks began in earnest during that war. Huge demonstrations of a wider peace movement condemned Ariel Sharon – Israel’s military chief – for his role in that war. A small but growing number of young people are now refusing all army service for Israel on political grounds and expressing their open support for justice for Palestinians. Two more of them – young women – have recently been thrown in jail. The times they are a-changing.

Excellent piece, David. May I point out to anyone reading that the ‘Lubavitch’ to which David refers are far more commonly known these days as ‘Chabad’ (the ch pronounced as in ‘loch’). Chabad really seem to have taken over many Jewish communities globally and are perceived as a friendly and joyous form of Chassidic judaism at home in the modern world. They are often individually personable. Their Chabad houses are visited by orthodox Jews travelling away from home, Jewish students and so on. But as David points out, they are hard-line Zionist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your blog post refers to Chabad as Zionists. Their position is more complex than this and more contradictory. They are not Zionists in a technical sense; they do not refer to the country as Israel (always “Eretz Yisrael”), they do not alter the prayers which they say on Israeli Independence Day (a key indicator among religious Jews as to whether they are Zionists or not) and their leader told his followers not to serve in the army. Nevertheless, your general point about Chabad is right; they favour nationalistic policies in Israel, oppose peace processes and more and more (male) Chabadniks are serving in the army. The reasons for this apparent contradiction are mostly theological.

LikeLike